1999, 2000

I was fortunate to take two creative non-fiction classes with Ray Lifchez, cranking out a three-thousand word essay each week. These two classes were my first close knit seminars and it was a glorious exploring the possibilities of the written word with my fellow students.

There is a trope where someone will claim that their liberal arts english course was the class that resonated the longest after their collegiate career. It’s hard to argue such a contention after being introduced to Invisible Cities and Labyrinths.

This piece was one of my favorites.

Moves

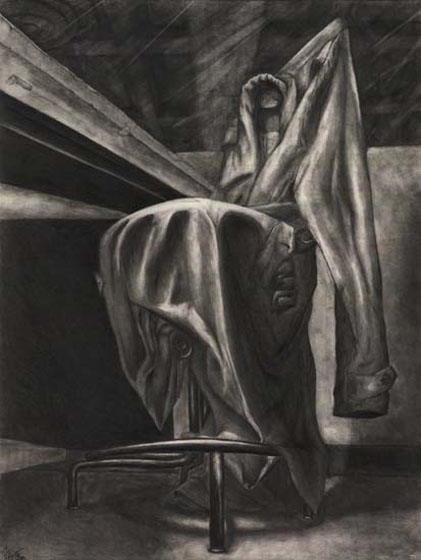

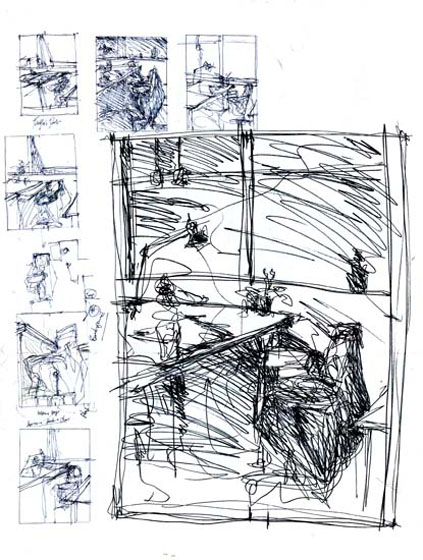

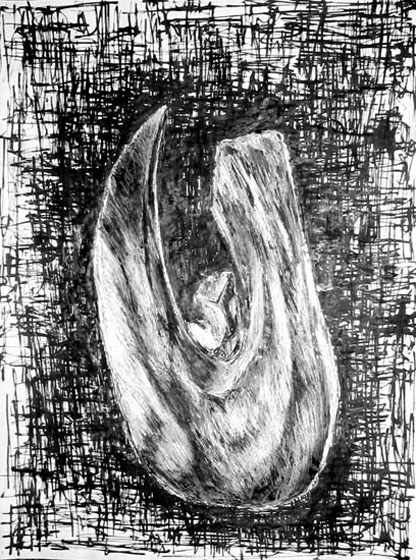

As I swing by my studio after class, I hear his music echoing from the opposite end of the hallway. I follow the noise and open the door to his ceramics studio. He has just started smoking a cigarette and waves me over to take a seat. It’s almost midnight, but he works hyped on nicotine, caffeine, and music. By the time I settle into a chair, he has finished the cigarette and was back to work. From my seat I have a full view of his collection, all in various stages. Due to a space crunch, he was shoved into the backroom next to the double doors. Air is a major problem, it floods through the doors’ gaps, drying out the clay very quickly. “No time to fuck with it.” This sort of problem for a plastic medium naturally creates a determined, purposeful rush. Compound this rush with loud music and a frenetic atmosphere overtakes this windowless room deep in the bowels of Wurster. His arms and hands dance among his tools and sculptures, while the rest of his body shakes to the music, rhythm, and beat. He jumps from one spot to another; water bottle in hand he cares for his flock of rapidly drying ceramics. As he unwraps and examines each piece, a wide range of emotions flitters across his face, each quickly transforming into another. As his pursed lips melt into an unconscious grin, he starts whistling to the music. The lips follow the melody but the rest of the body gyrates with the beats bouncing between the walls – “one and two and three and four and one and two and three and four and one and two.…” The music clutches the room in a tight grasp. This secluded place intensifies every element within it. In this primal, cave-like environment, one’s body reacts unconsciously to any stimulus. At times he crouches, eyes piercing through the shadows; others times he squats, examining the bottom of a sculpture. He steps back and stands, trying to create a distance between himself and his work. Like a cat stalking its prey, his body is always at attention as it hovers around his sculpture. He never sits. A primordial sense of struggle is awakened in the modern soul – a sculptor must not only fight materials and gravity but he must conquer his own physical and mental fatigue. It is a continual battle between one’s artistic conscience and one’s level of endurance. As our ancient fathers pursued their quarry, he participates in a hunt of the most aggravating sort – one where the prey is always a step ahead, looking back, teasing you to give up. In a trance, he examines a pair of legs waiting for a body to support. Satisfied, he jumps up, unwraps another disembodied leg, sprays it, feels its moisture, and rewraps it. He turns, drinks his grape soda, looks into space and moves back among his collection. He grabs some clay, rolls it between his hands, shakes his head, and throws it back into its bucket – “not yet.” Stepping back, he stares intently at the next piece, a bust of a young man. He rubs his hands against his pants, pulls out a tool, dons a mask, and shaves its rib cage. Figures are made of shapes, shapes are made of lines – it all returns to the line. He stands back and eyes the bust from left to right. Content, he whips out a small head from a plastic bag, sprays it, sponges its hair, looks at it for a moment, flips the bag open, and shoves it back as quickly as it came out. With that, he turns around, grabs a cigarette and lights it. For the last half hour he has not noticed my presence. When he finally sees me, he looks shocked but doesn’t stop. Even when he stops working, he continues appraising his pieces. His gaze fixes upon a sculpture while the body undulates to the syncopated rhythms. “I can see you!” he says to the half-finished figure. A smile creeps onto his face. He peers intently as smoke climbs up to the ceiling and ashes drop onto the concrete. His blue t-shirt hangs loosely around his torso, shifting every time his hand swings up to his mouth. As the CD ends, he starts another CD, another cigarette, and another figure. As one hand holds the burning cigarette, the other hand begins working a lump of clay. His energy is relentless; he has yet to take a seat since I’ve entered. It doesn’t stop.